The Irish Potato Famine is one of the great sad events of the 19th century. It lasted from 1845-48 though its effects were felt for much longer. During that time of the potato famine Ireland lost more than a quarter of its population. Out of about 8 million inhabitants one million died and another emigrated. Here we will tell you the story briefly and pay tribute to those who died.

Ireland Before the Famine

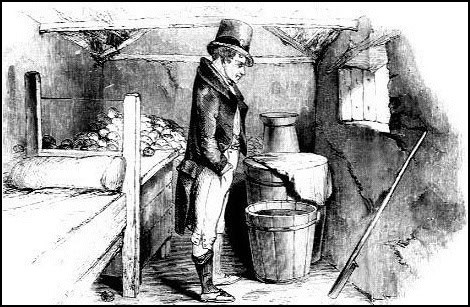

Before the Famine Ireland had a population of about 8 million. This was the population of the whole island since back then there was no Northern Ireland and southern Ireland. The majority of the arable land belonged to English or Anglo-Irish landlords, many of whom lived in England. They in turn parceled out their land to Irish tenants. Most Irish tenants held small plots of land for which they paid rent. Some landless laborers would seek work among the tenants. In return they would get a small garden to plant potatoes for their own needs and a small place to live. These living spaces were often nothing more than a one room mud hovels where the family lived together with whatever livestock it may have had.

Potatoes for Every Meal

The potato was the main food of the poor. The potato was introduced for cultivation in Europe from America in the 16th century. It made its way into Ireland and became the principal food of the poor. Other crops were also grown but were usually too expensive for the landless laborers of the small farmers. Expensive crops were usually exported.

Before the coming of the Famine Ireland was among the poorest countries in Europe. Yet the people enjoyed fairly good health. The potato is a very nutritious vegetable that provides many of the essential nutrients and in some way the small Irish farmer, though very poor, often had a better health and nutrition that many of his counterparts in other countries in Europe.

Regional Crop Failures

Ireland had experienced potato crop failures on a number of occasions before 1845. But they were regional and limited to one season. A good harvest in one county meant that even if there was a crop failure in another there were still enough potatoes to go around and famines were avoided. All this changed beginning in 1845.

Cause of Irish Potato Famine

In the previous page we talked about Ireland before the Famine. Now we look at how the Famine came about.

The problems began in September 1845. The cause of the potato Famine was an airborne fungus called phytophthora infestans, which became commonly known as “blight”. It seems to have originated in America and was brought over to Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland on ships plying the trade routes, and then carried with the winds.

The seeds would fall on the leaves of the potato plant which would then begin to turn black and rot giving off a horrible smell. The rotting leaves would provide nourishment for the fungus which would grow and spread by the wind to other potato plants. A few infected plants could in turn infect thousands of others throughout large areas.

The blight affected not only the leaves but also the potatoes. When dug out they at first appeared in good order, but would rot within days. Most of the crop of the 1845 harvest was destroyed. While the scale of the disaster was great, despair had not yet set in. The Irish had learned to weather past smaller famines and thought they will weather this nationwide one too.

Meanwhile, prime minister of Britain Robert Peel, becoming aware of the potato famine purchased shipments of corn and redirected them to Ireland. These shipments helped to alleviate the suffering, but by no means solved the problem.

The Difficult 1846

As the summer of 1846 approached people were optimistic. Having weather the worst they looked forward to a good harvest. They didn’t think that the disaster of the previous year would be repeated. Initially the plants looked healthy. But soon the signs of the blight appeared again and spread throughout the island. The crop was totally destroyed.

The second half of 1846 and the first part of 1847 were probably the worst months of the Famine. As the government changed in London, the cheap corn shipments stopped. the new government tried to provide an income for the destitute by launching a railroad building scheme and other public projects. Then soup kitchens were launched. But even such projects failed to solve the problem.

1847 Onwards

The harvest of 1847 was blight free. But that did not mean that everything was back to normal. Because only few healthy potatoes had been planted the harvest was only a quarter or the normal yield. Furthermore, in 1848 the blight returned with a vengeance destroyed nearly all the crop again. It would be several years before production reached normal levels again and things came back to anything resembling normalcy.

The Irish Potato Famine – Consequences

The Aftermath

In two previous pages we looked at Ireland before the Irish Potato Famine, and at the Famine itself. Now in part three, we look at the consequences of the great Irish Famine.

Depopulation

While from 1849 onwards there was some harvest, the repercussions of those difficult years were to be felt for decades. In fact, the impact is still felt today. Here are some of the most important.

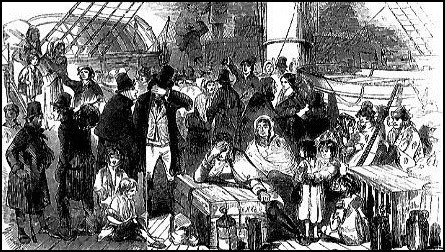

During the years of the Great Famine and its aftermath about 1 million people died, not so much from starvation but by diseases associated with malnourishment. About 1 more million emigrated, most to America but many also to Britain, Canada and Australia. The immigrants were not always welcomed. The sight of shipload after shipload of destitute, impoverished and malnourished immigrants raised fears of unemployment, crime and disease among the receiving populations. The immigrants had a hard time starting a new life. But they eventually settled in and because the founders of prosperous communities. They bean sending money back which in turn helped the local economy survive.

Social Unrest

The Famine caused considerable unrest leading to a rebellion in 1848. The social fabric of society was changed. Many of the poorest tenants were evicted from their homes and tiny farms because they could not pay the rent. Moreover there was a widespread feeling that the government was not doing enough to contain the Famine. Social unrest grew and in 1848 erupted into violence. The uprising was quickly contained but disaffection continued. As the new immigrants, especially in America, settled down and became affluent, they began to envision an Ireland free from British control. While it would be too much to say that the Famine laid the roots for what eventually became the Republic of Ireland, it certainly helped alienate the Irish from the British.

Today

A visitor to Ireland today will come across many memorials to the victims of the Great Famine scattered throughout mostly in the Republic, but also in Northern Ireland. The Famine is one of the very sad pages in the history of this land, indeed one of the very sad pages in the history of Europe.